Colóquio Internacional

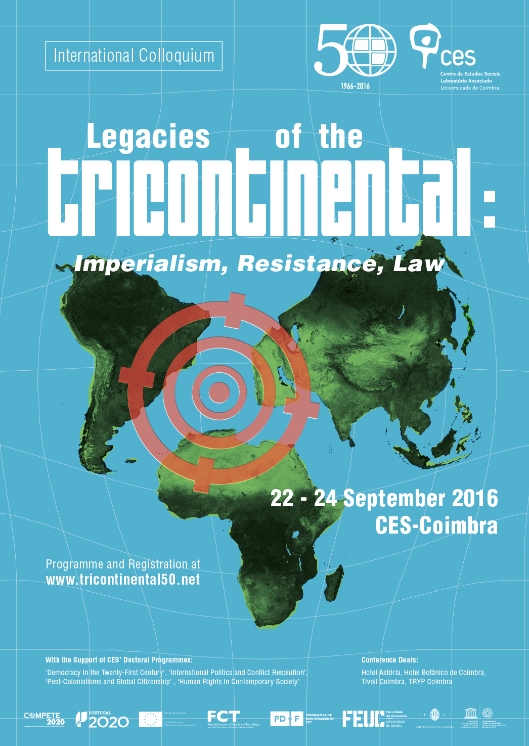

Legacies of the Tricontinental: Imperialism, Resistance, Law

22 a 24 de setembro de 2016

Sala 1, CES-Coimbra

Enquadramento

The 1966 Solidarity Conference of the Peoples of Africa, Asia and Latin America, or Tricontinental Conference as it is better known, remains one of the largest gatherings of anti-imperialists in the world. More than 500 representatives from the national liberation movements, guerrilla movements and independent governments of some 82 countries gathered in Havana, Cuba to discuss the burning strategic questions confronting the anti-imperialist movement of the day. Amongst the delegates were some of the most important figures in the anti-imperialist movement including Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, Sálvador Allende and Amílcar Cabral.

Building on the earlier 1955 Bandung Conference and 1964 UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the Tricontinental represented the extension, into the Americas, of Afro-Asian solidarity begun at Bandung. As such, The Tricontinental marked a highpoint in the emergence of a non-aligned movement and the construction of a Third World anti-imperialist project. At the same time, the Tricontinental represented a break with those earlier efforts. Whereas Bandung was a relatively modest affair, in which the various political currents in the Third World came together to articulate a minimum programme, the Tricontinental was avowedly more radical, explicitly attempting to align anti-imperialism with a wider challenge to capitalism. In the words of Mehdi Ben Barka, Moroccan socialist leader and organiser of the Conference, the Tricontinental aimed to ‘blend the two great currents of world revolution: that which was born in 1917 with the Russian Revolution, and that which represents the anti-imperialist and national liberation movements of today’. Indeed, the Conference featured leftist guerrillas who were busy fighting against their own Third World governments.

In keeping with this radical orientation, the Conference condemned imperialism, colonialism and neo-colonialism, declaring its solidarity with the Vietnamese struggle against the United States. The Conference called more widely for solidarity amongst the radical currents in the Third World and debated what role they would take in relation to the United Nations. In so doing, the Conference created a huge stir in the developed world, becoming the target of numerous attempts at subversion.

The Tricontinental was a huge influence on the development of the later Non-Aligned Movement. In fact, its legacy includes a whole host of developments. On the legal front, General Assembly Resolutions such as the Friendly Relations Declaration and the Declaration of the New International Economic Order flowed directly from the Conference. Similarly, the ideas of military solidarity which animated the Conference bore fruit in events such as Cuba’s 1973 intervention in Angola against Portuguese colonialism.

However, despite this importance, the Tricontinental has received very little attention. Scholarship has tended to focus on the relatively modest demands of the Bandung Conference, and neglected the political cleavage represented by the Tricontinental. This has been especially true in international legal scholarship. Thus, whilst the Third World Approaches to International Law movement has paid close attention to the legal arguments of the Third World during the anti-colonial movement, the Tricontinental has not figured heavily in this account. This is representative of a wider erasure of the radical wing of the Third World movement from international legal histories. Yet this means that a key element of the Third World story has been missed. Without paying due attention to this tendency it becomes impossible to understand the development of politics in the Third World. Moreover, the rich heterodox theoretical and political perspectives put forward by the Tricontinental remain lost to us.

The 50th anniversary of the First Tricontinental is an opportunity to reflect on its enduring political, legal and economic importance. We wish to consider both the historical importance of the Conference and its role as a key site for Third World project, as well as its legacy, both intellectual and political, today. Of particular concern is the role of the Tricontinental and ‘tricontinentalism’ in shaping theoretical currents including TWAIL, postcolonialism and Third World Marxisms, as well as conceptualisations of global subalternity and anti-imperialism and concrete forms of South-South cooperation and solidarity.