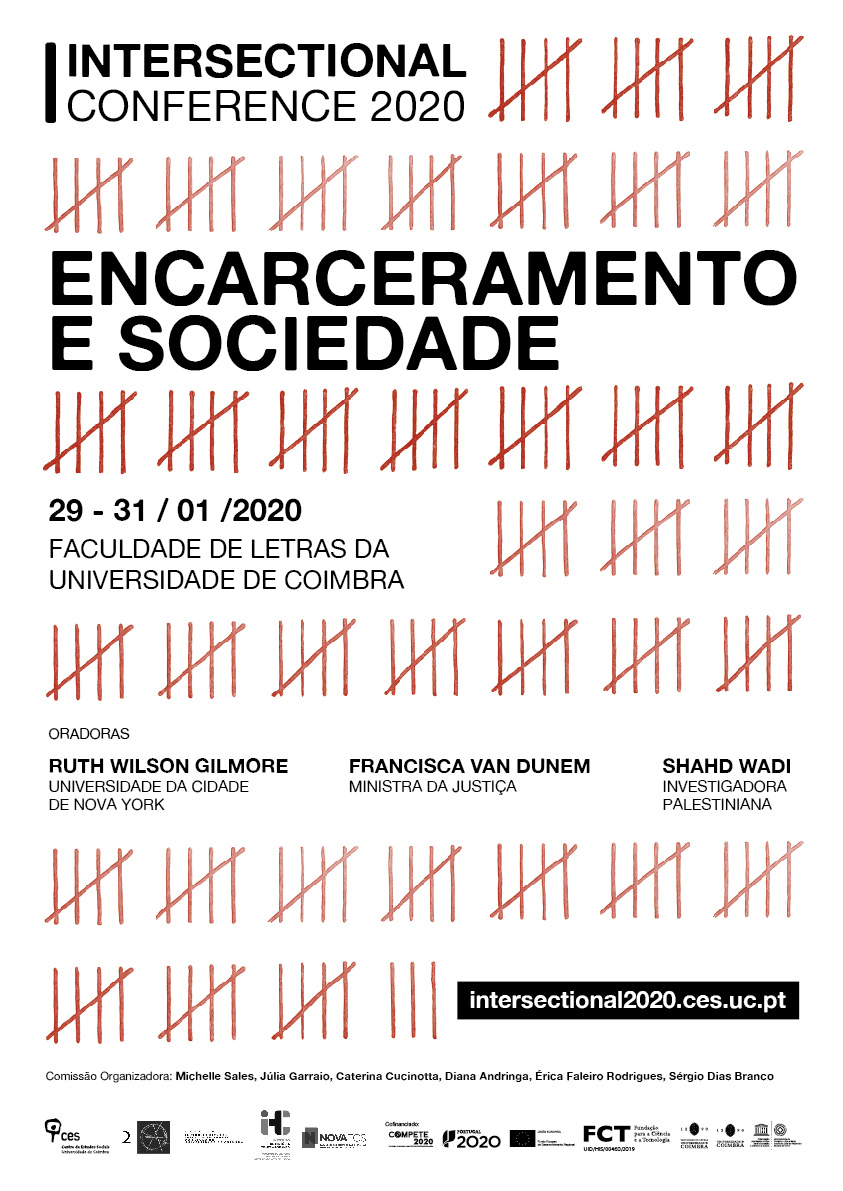

I Intersectional Conference 2020

Encarceramento e sociedade

29 a 31 de janeiro de 2020

Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Coimbra

Apresentação

O filósofo afro-americano Charles Mills refere que a supremacia branca ocidental criou um sistema de poder não-nomeado que carrega consigo uma estrutura social e política que permite o exercício pleno de um Estado e de um sistema jurídico racializados, capaz de determinar e legislar sobre a vida e a morte dos copos subalternizados. Neste contexto, a branquitude como sistema de poder instituído determina, em países com um historial de escravatura e/ou colonização, a hegemonia dos brancos em todas as esferas da sociedade e impõe, do outro lado, lugares sociais marginalizados e subalternizados para os corpos racializados dos negros, dos latinos, dos não-brancos e das minorias em geral. Um dos lugares reservados a corpos subalternizados é a prisão.

Veja-se nomeadamente o caso dos EUA. Durante as últimas quatro décadas, temos assistido ao crescimento desproporcional das taxas de encarceramento, apesar de uma redução do número de crimes. Como afirma Michelle Alexander, através das políticas que produzem o encarceramento de massa da juventude negra neste país, perpetua-se a negação de uma cidadania plena para os Afro-Americanos. Essa negação está na base da fundação do país, que nasceu, como sabemos, não apenas na conquista, subjugação e mesmo extermínio de povos indígenas, mas igualmente na instituição da escravatura e exploração dos corpos racializados. Investigadores/as e ativistas como Angela Davis apontaram precisamente para a exploração do trabalho nas prisões por empresas privadas no presente como um fenómeno revelador dos enredamentos e das convergências entre capitalismo, Estado moderno, racismo e meios de comunicação.

O caso do Brasil é semelhante. Segundo dados do Infopen, 94% da população carcerária são homens com idades até 29 anos, entre os quais 65% são negros ou pardos, o que indica como o “sistema industrial carcerário” mantém uma relação seminal com o passado colonial escravocrata e racista do país.

Mesmo em Portugal, um dos países europeus com mais baixo índice de criminalidade, as taxas de reclusão estão atualmente acima da média, revelando uma situação de sobrelotação prisional que chega, nalguns locais, aos 200%. A lei portuguesa não permite fazer uma categorização etno-racial da população prisional que nos permita visibilizar, através de dados estatísticos, em que medida o sistema judicial e prisional português é permeado por discriminações raciais. A simples observação aponta, no entanto, para uma percentagem de negros e ciganos na população prisional muito superior à sua representação na população em geral.

A lógica da exclusão e marginalização assente em processos de racialização não está confinada ao espaço carcerário; estende-se a todo o tecido social e aparece com violência seja em espaços rurais seja em espaços urbanos.

Entendemos, no entanto, que o caso português, como outros casos europeus, têm características bem diferentes daquelas dos Estados Unidos da América do Norte e de países da América Latina, onde, tendo a independência sido obtida por descendentes dos colonizadores, a discriminação prolongou quase naturalmente aquela da escravidão. Na Europa, nomeadamente em Portugal, houve um nítido corte temporal entre a presença de escravos negros e a imigração que se verificou, em muitos países, nos anos 60 e, em Portugal, sobretudo a partir de meados da década de 70.

Mais: se nos EUA e no Brasil a independência foi feita pelos descendentes dos colonos, nas colónias europeias em África a independência foi imposta pelos seus povos, provocando uma interrupção clara no sistema de escravatura/trabalho forçado e dando aos cidadãos desses países que imigram para a Europa – nomeadamente para a antiga metrópole colonial – um estatuto bem diverso do dos afro-americanos e que julgamos importante ter em conta nesta Conferência. E em que não é possível esquecer a memória ainda bem presente de conflitos – que em Portugal revestiram, em três das colónias, a forma de luta armada – que terminaram com a vitória dos povos das colónias.

Como nota Jaime Amparo, cidades como São Paulo e Rio de Janeiro podem ser pensadas como sendo anti-negros e negras, pois há um forte aparato social de construção da exclusão social, da evasão escolar e do consequente aprisionamento e marginalização da vida dos corpos negros e não-brancos instituído por um Estado racial e reproduzido pela mídia racista.

As mulheres racializadas em espaços marcados pelos legados do colonialismo europeu (mas não só!) enfrentam assim múltiplas formas de opressão. É assim que mulheres negras afro-americanas criaram, ainda em finais do século XIX, a National Association of Colored Womens Club, logo após ter surgido a primeira associação de mulheres feministas nos Estados Unidos, que reunia mulheres de classe média branca. Unidas pela luta política contra o racismo, e sob o lema “lifting as we climb”, as mulheres negras afro-americanas reúnem-se com a forte consciência de que a luta contra o machismo se impunha de forma distinta entre mulheres brancas e negras. Nesse sentido, foram pioneiras ao apontarem para a necessidade de entender a opressão e exclusão das mulheres pelo mundo como sendo marcada por uma diversidade de fatores, que passam pela classe social, poder económico, pertença étnico-racial, entre muitos outros.

Davis chamou atenção para o fato de, nos EUA, uma mulher negra afro-americana ter quatro vezes mais probabilidade de ser presa do que uma mulher branca. Notou também como a relação das mulheres negras afro-americanas nos EU com o sistema de saúde, habitacional e escolar, por exemplo, está fortemente marcada pela cor da pele. Outras minorias e outros corpos vulneráveis – LGBTQI, pessoas com doenças mentais, migrantes, entre muitos outros – também sofrem com mais intensidade e violência as consequências de um sistema punitivo que, mais que um meio de limitar o ‘crime’, revela-se um poderoso instrumento de controle social. Esta situação deve ser central na discussão urgente sobre abolicionismo penal.

Esta conferência pretende, através de uma abordagem interdisciplinar, aprofundar o tema mais amplo deste encontro “Encarceramento e sociedade”, inscrevendo-o nos espaços marcados pelo colonialismo europeu e seus legados. Pretende reunir contributos de diversas áreas, como História, Sociologia, Religiões, Artes e Humanidades, valorizando abordagens interseccionais que cruzem questões de gênero, de classe social, de raça, de nacionalidade e de etnia.

Tópicos a abordar:

- espaços sociais e vigilância

- democracia e poder

- segregação

- gestão prisional

- direitos humanos

- território

- violência

- branquitude

- biopoder

- Heranças da escravidão

- Abolicionismo penal

- Feminismos

- Representações artísticas e culturais

- Capitalismo e escravidão

- Tráfico de pessoas

- Escravidão nos tempos modernos

Este evento é de entrada livre, até ao limite dos lugares disponíveis

Referências:

Alexander, Michelle (2010). The New Jim Crow. Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York: The new press.

Amparo, Jaime (2018). The Anti-Black City: Police Terror and Black Urban Life in Brazil. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Davis, Angela (1981). Women, Race, & Class. New York: Random House

------------------ (2003). Are Prison obsolete? New York: Seven Stories Press.

------------------ (2005). Abolition Democracy: Beyond Prisons, Torture, and Empire. New York: Seven Stories Press.

Mbembe, Achille (2013). Critique de la raison nègre. Paris: La Découverte (« Cahiers libres »).

Mills, Charles (1997). The Racial Contract. Ithaca: Cornell University Press

Stemen, Don (2017). The Prison Paradox: More Incarceration Will Not Make Us Safer. New York: Vera Institute of Justice

Organização:

CEIS20 - Centro de Estudos Interdisciplinares do Século XX (UC)

CES- Centro de Estudos Sociais (UC)

IHC - Instituto de História Contemporânea (NOVA - Lisboa)

FLUC - Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Coimbra

Comissão Organizadora:

Michelle Sales (CEIS20)

Júlia Garraio (CES)

Caterina Cucinotta (IHC)

Diana Andringa (CES)

Érica Faleiro Rodrigues (IHC)

Sérgio Dias Branco (CEIS20)

Comissão Científica:

Ana Cristina Pereira, Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade (CECS)/ Universidade do Minho

Ana Oliveira, Centro de Estudos Sociais (CES)

Aurora Almada e Santos, IHC - Universidade NOVA de Lisboa

Carla Cerqueira, Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade (CECS)/ /Universidade do Minho

Caterina Cucinotta (IHC)

Diana Andringa (CES)

Érica Faleiro Rodrigues, Instituto de História Contemporânea, IHC - Universidade NOVA de Lisboa

Fernanda Bruno, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro

Júlia Garraio (CES)

Julião Soares Sousa, Centro de Estudos Interdisciplinares do Século XX (CEIS20)

Marisa Gonçalves, Centro de Estudos Sociais (CES)

Michelle Sales (CEIS20)

Pablo Assumpção, Universidade Federal do Ceará

Rita Luís, IHC – Universidade NOVA de Lisboa

Rui Bebiano, Centro de Estudos Sociais (CES)

Sérgio Dias Branco, Centro de Estudos Interdisciplinares do Século XX (CEIS20)